When I first began my college course in Writing Theory and Ethics, I had little to no intention of writing down my own theories of writing outside the class, thinking that theories were only set aside for academic exercises or dissertations. But now that I have taken this class, I see that I’ve been writing down my theories ever since I began my novels in high school. It was just a matter of recognizing my own patterns of thought and seeing those patterns play out in my fiction.

When I took classes in literary theory and creative writing, I began my own diary in which I revisited events of the day and sometimes jotted down clips of creative writing that I didn’t use for my assignments. As I matured in my writing and pursued my love of novels, I began to see patterns in how I thought and how I formed my stories. Sometimes those stories followed a similar motif, such as how I view a hopeful versus a happy ending and how I insinuate my faith into my writing so that my Christianity appears normal rather than contrived.

As I added my minor in journalism, I began to condense my diction and form my style with more action-packed syntax. Now I see the world through a journalist’s eyes, replacing my prepositional phrases with clear-cut nouns and verbs that grab my readers’ attention.

But my love is novels, and though the economy has shifted in favor of technical and journalistic writing, I have coupled my love for novels with my skill in journalism and have found social media to bridge the gap between classical literature and contemporary trends. It is actually in the ubiquitous Facebook and Twitter that I have begun establishing my presence as a writer, and as I tweet, text, and post “likes” on my statuses, I am beginning to see that the trends in our culture are helping me build a happy podium on which I can establish my career as a writer.

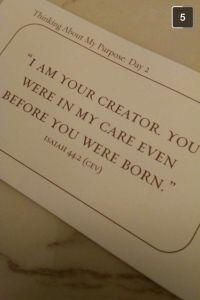

Throughout the journey of developing my personal literary theories, I have delved into greater strides of what I truly believe to be my own theories on faith, fiction, and journalism. In all my writing, I’ve noticed that I carry a thread of hope in my work. Whether it’s in newspaper articles, novels, or academic prose, I’m always writing with the clear vision that my readers will glean hope from my writing, and it’s because of my love for and belief in God that I’m able to portray hope in my writing and see this whole world as a reflection of His glory and workmanship.